We all have our notions of Queen Victoria, even as the Victorian age recedes further into the past. It’s an obscure song from Leonard Cohen which I’ve long associated with her:

Queen Victoria,

My father and all his tobacco loved you,

I love you too in all your forms,

The slim and lovely virgin floating among German beer,

The mean governess of the huge pink maps,

The solitary mourner of a prince.

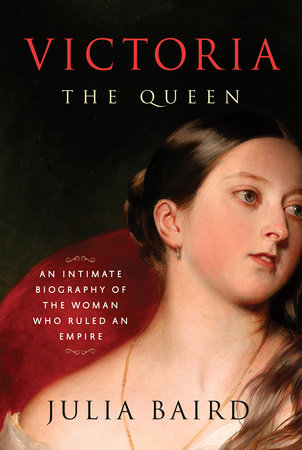

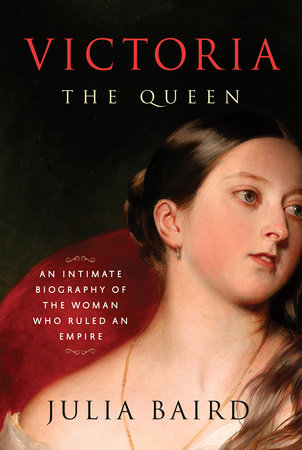

Cohen was right: there are many Victorias, public and private, old and young. Few have lived a more documented or contested life, making her a formidable biographical subject. It didn’t stop ABC journalist Julia Baird taking on the challenge and after eight years of work, her Victoria: The Queen was published in November.

Victoria is a superb biography, the kind I aspire toward, compulsively readable and intelligent. The combination of journalist and historian – Baird has a PhD in the discipline – is an ideal one for a biographer. She writes vividly, precisely, and wisely as she narrates the development of Victoria through life stages and how she became the different Victorias, some mythical, some misunderstandings, some true but in need of nuance. One of the surprises for me, for example, was to discover that Victoria began life as a Whig, opposed to the Tories; it was fascinating to see her political transformation as the politics of Britain changed over the century and she finished her life as the more expected ardent Tory, close to Disraeli and hating Gladstone. The “mean governess” is only part of the story, and a fun-loving, opinionated, passionate woman emerges in the biography. Some cautious biographers avoid interpretation let alone judgement; others are far too confident and dogmatic in their judgements. Baird is a courageous and wise interpreter of her subjects. “Victoria’s passionate fits came and went, but Albert’s anger was white, cold, and enduring. He was willing to inflict pain on his wife.” She captures the complexity of Victoria’s character, her goodness and her faults in an evenhanded way.

The biography is structurally accomplished in its combination of the chronological and thematic. Each chapter takes us forward a little in the span of Victoria’s long life, but has its own mini-narrative ranging over the span of a particular incident, theme, or relationship. It’s one of the difficult and essential things to get right in biographies; biographies which are too strictly chronological tend to fall apart as narratives, constantly broken up with the next development in the myriad of “subplots” that are developing in any subject’s life at any time.

Most chapters begin with a scene, a fraught process in biography as there is rarely enough sensory detail to build up a scene purely out of historically verifiable material. Thus in chapter 11, Victoria’s wedding, Victoria is lying in bed before the wedding. “She closed her eyes and thought of the preparations humming across the city.” The preparations she imagines are all historically sourced, although in this case the device feels a little clumsy to me. However, it’s probably more a question of what the reader finds permissible in biography than anything else. Some other scenes work perfectly and it’s part of the biography’s appeal that Baird has used the approach.

I am in admiration of Baird’s grasp of nineteenth century British (and wider) history. To read the biography is to be given an accessible primer in the period, as Victoria was involved in everything from the social upheaval resulting from industrialisation to the Crimean War to the emergence of a unified Germany. Baird shows great skill in narrating complex historical events in a way which is gripping but not simple.

The amount of research involved in any biography is immense, but this book must have involved more than most. The volume of primary and secondary material is huge. Despite redactions, burnings, and the losses of time, many of Victoria’s letters and diaries remain, and that is only the first layer of material. The biographer has to be on top of it all and then have the instincts for what is important and how their reconfigurations and reinterpretations will add something new. One of Baird’s great discoveries – found in a doctor’s diary – is an account of Victoria and her confidante, John Brown, peeking under each other’s clothes. The temptation is to trumpet the revelation, but Baird avoids this completely, narrating her breakthrough material in a straightforward way and letting it speak for itself. I admire that, and would have allowed her considerable more trumpeting.

I really enjoy Julia Baird’s hosting of ABC TV’s the Drum, where she brings out the best from her guests and steers the conversation well. (I’ve often wondered at her politics, given she comes from Liberal Party royalty but doesn’t seem conservative in outlook; turns out her Twitter profile tells all, at least for those better-read than I was: she is a “Mugwump.”) It was interesting to hear her on Philip Adams’ Late Night Live in the guest chair, speaking passionately and articulately about her subject, showing a different side of her character. She spoke then of the challenge of accessing the royal archives and how it was only the intervention of the former governor-general which secured her access. But her obstacles were even greater than that: she wrote movingly last year about living in the shadow of death after a cancer diagnosis, only to come through. I hope she continues to write for the New York Times and host the Drum, but most of all I hope she continues as a biographer.